Research

Here, you’ll find a (hopefully) accessible background and a summary of my work on my major research projects.

Previous Projects

Characterizing black hole X-ray binaries (BHXRBs) with Chandra

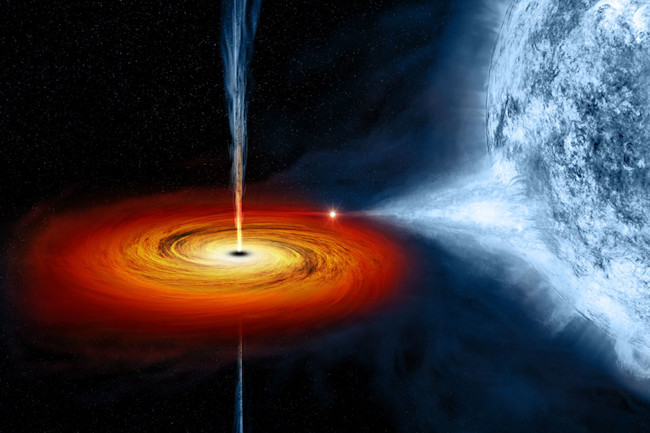

Stellar-mass black holes are most often observed via interaction with a companion star, which orbit one another in what’s known as an X-ray binary (XRB). These systems earn their name from the high-energy emission generated when the black hole accretes material from its companion, observed here on Earth as X-rays by space-based observatories like Chandra.

All compact objects – black holes, neutron stars, and white dwarfs – have the capacity to form X-ray binaries due to their strong gravity. Black hole XRBs in particular are known to cycle through distinct emission states tied directly to their accretion rate. Studying in detail the energy signature and variability of a particular XRB – especially as the system evolves through multiple emission states – can reveal much about the nature of the system itself, their gravitational effects on their environment, and the high-energy physics powering their emission.

The detailed analysis required to confidently classify and characterize these systems is prohibitively time-consuming for large samples, but with each newly-examined system comes improved constraints to the BHXRB population’s parameter space, making them easier to identify and study. As part of my 2021 honors thesis in the Wesleyan University astronomy department, advised by Prof. Roy Kilgard, I performed such an analysis for the ~80 brightest (in flux) extragalactic X-ray sources outside of the Local Group. The initial sample comes from the Kilgard group’s database of 45,000+ observations of such sources from the Chandra archive.

In my thesis, I identified 11 candidate XRBs, the majority of which have not been studied in detail in the literature and many of which are candidate XRBs. With the data from these observations, I suggest a new photometric method for identifying and classifying ultraluminous X-ray binaries with Chandra. I presented this work as a poster at the AAS 237 in January of 2021.

|

|---|

| An artist’s rendition of the HMXB Cyg-X1, one of the first discovered and most well-studied XRBs. (Credit: NASA, CXC, M. Weiss) |

Simulating the Solar Gravitational Lens (SGL)

Light tends to take the shortest path as it travels through the universe. When it encounters a massive object (e.g. a galaxy,or a cluster of galaxies), the shortest path becomes a curved path, as spacetime itself becomes warped in the presence of matter. This means that, from here on Earth, we sometimes observe the light from objects behind other massive objects like galaxies, as the path of the light is curved around the outside of the object by gravity. This phenomenon is known as gravitational lensing.

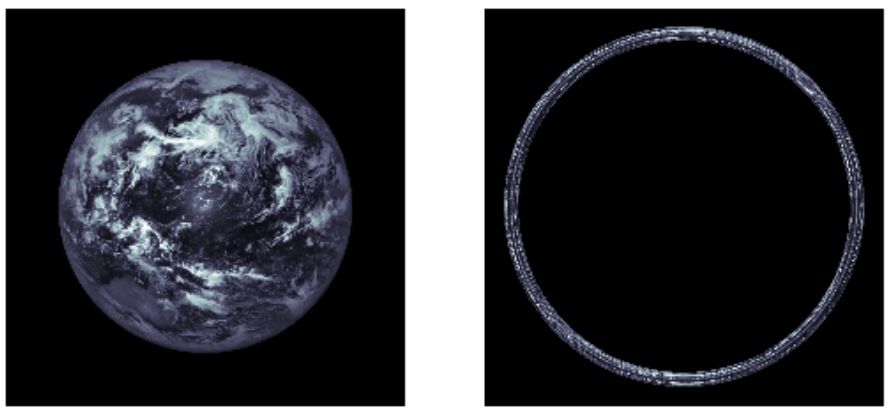

As the name suggests, astronomers often take advantage of this phenomenon, using massive objects as “lenses” to enhance the data that we get from these objects, much like a telescope. While galaxies and galaxy clusters boast the most mass and are usually used for these kinds of studies, any massive object can theoretically act as a lens in this way, including stars like our own Sun. If we were to place a telescope at about 550 astronomical units (about 50,000,000,000 miles!) from the Sun and align it perfectly with a target – say, an exoplanet – we would see the light from the planet immensely magnified and spread out in a ring around the outside of the Sun. This Einstein ring would contain a high-resolution image of the surface of the exoplanet, equivalent to a modern sattelite image of the state of Connecticut. Such a telescope is in the planning stage, and is known as the Solar Gravitational Lens (SGL).

The problem is, the image is warped into this Einstein ring and needs to be reconstructed, which is easier said than done. My early undergraduate work, advised by Prof. Seth Redfield, focused on this problem. I developed SunTracer, a relativistic raytracer which simulates images as they would be seen by the SGL. This was the first step toward a deconvolution method for the aforementioned problem, meant to generate a training set for a machine-learning algorithm which would deconstruct the original exoplanet images from these Einstein rings.

I chose to transition to a new project after developing SunTracer, and the deconvolutional methods for these images are being worked on by other, more qualified parties, namely Dr. Slava Turyshev and Dr. Victor T. Toth at JPL; interested parties may read the SGL group’s NIAC Final Report. Or, for a lighter read, my paper from my talk on the subject at KNAC in fall of 2019.

|

|---|

| Images of a habitable planet as seen by the SGL. Here, I utilized RGB data from NASA’s EPIC camera aboard the DSCOVR satellite as the source for SunTracer, which warped the image into an Einstein ring. (M. V. Tea) |